Back to the shack: How restaurants are rediscovering street food

If you were a budding chef owner with a passion for food but not enough cash for an actual place, you’d buy a van, do your best at the local markets, rave about flavour and produce and authenticity and international influences, Instagram the hell out of it, and hope that people loved it as much as you did.

Then, once you’d made a name for yourself, you’d maybe announce a pop-up residency at a pub, and if that went well – boom, you’d open a permanent place. You’d made it.

Think Pizza Pilgrims, Rosa’s Thai Café, Pitt Cue Co, MeatLiquor, Homeslice, Tapas Revolution, Lucky Chip, Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen…and hundreds more. A high proportion of the UK’s up-and-coming casual brands started in a market truck, and graduated to an actual restaurant or five.

This trend was backed by consumer research: studies such as those shown in Santa Maria’s Street Food Report in 2014 found that 68% of Britons thought street food had introduced them to new flavours and 80% liked its international influences, with casual dining brands responding by bringing out reams of street-inspired options such as pulled pork sandwiches, Korean kimchi burgers, and easy-to-eat gyozas and empanadas.

Similarly, Horizons’ 2015 Menu Trends report found that high street brands were adapting their menus to incorporate street food influences.

And yet, even the new permanent-site graduates couldn’t quite shake the idea that maybe, they’d left their casual insouciance behind. Despite – or perhaps because of – its impermanent nature, street food never lost its cool.

Because as food markets in the UK proliferated and expanded – Hawker House, Kerb, Urban Food Fest, Leeds Trinity shopping centre, Manchester’s The Kitchens, and many more ‒ and new brands quite literally popped up every week, restaurants gradually realised: a permanent location may add weight to your brand, but it could never be as fancy free as a travelling offer.

Now, it’s clear: restaurants are going back to their roots, and some of the brands developing street food offers never even started there in the first place.

Far from staying safe in houses, street-to-site now goes both ways, as innovative groups look to capitalise on the safety of their permanent locations as well as capture the street cred that a van can bring.

Back to the streets

Some groups, such as the Indian food concept Kricket, merge the two ideas, with founders Will Bowlby and Rik Campbell opening a 20-cover site within the louche, relaxed street food-style space that is Pop Brixton. Restaurants are truly street-bound.

Street food has continued to see innovations, with Pop Brixton, Jonathan Downey’s Street Feast, the 2015 £3.5m crowdfunding bid from Downey and Henry Dimbleby to launch a permanent street food market in London, named London Union, and this year’s first ever Just Eat Food Fest in London.

Located in Shoreditch’s Red Market at the end of July, the latter event brought together dishes from around the world – including Caribbean, Vietnamese, Japanese, American and Italian.

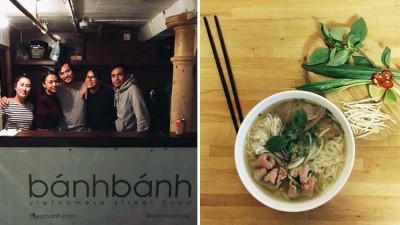

Those familiar with the city’s vibrant food scene will recognise the styles on offer: smoothies and juices, Vietnamese banh mi sandwiches, ribs and burgers, and wood fired pizzas. So far, so expected.

But a closer look at the line-up also reveals dim sum from Ping Pong, American sandwiches from Red Dog Saloon, Indian food from Gaylord, and doughnuts from Dum Dum Donutterie.

Real restaurants

Far from meandering vans or kiosks, these are actual, well-established restaurants.

In the case of Ping Pong, it’s a global chain with eight London venues, originally started by seasoned restaurateur Kurt Zdesar. Red Dog Saloon has three central London sites, and Gaylord is the family-owned London Fitzrovia institution, which first opened an incredible 50 years ago in 1966. Three-site sugar specialist Dum Dum Donutterie even has an outlet in high-end department store Harrods.

When you’ve got established sites from Wembley to Westfield, and certain commentators have even dared suggest that street food might have lost its sheen (The Guardian’s Paula Cocozza asked if the “street food revolution had run out of road” as far back as 2014), why would you bother with one outdoors shack?

Art Sagiryan, chief executive at Ping Pong explains: “Momentum and excitement around the street food trend is still rife with young consumers and it’s essential that restaurants wanting to engage with this audience keep up.”

Sameer Berry, general manager at Gaylord agrees. “Street food plays a major part in our culture, and it’s good for restaurants to understand this, and show off that they can do it too.”

The winds of change

Yet, despite street food’s ongoing appeal to young people, it seems a stint on the streets isn’t just about old brands trying to stay cool.

The transient nature of shacks allows groups to test new ideas without committing to a complete change in menu or style, or compromising the central brand message.

As Paul Hurley, founder of Dum Dum Donutterie, says: “At street food events there tends to be a bit of everything, so it gives the customer a change to try things. There’s a greater selection and you can see people’s reactions. Recently we loved the response to our new ‘Crone’ – the croissant doughnut ice cream. They seemed to really enjoy it.”

And whereas Dum Dum Donutterie might take their usual menu from shop to street, other groups often take the opportunity to innovate. “Street food allows us to be more playful with our menu,” says Berry from Gaylord. “Our street food is quicker, and filling, and often more experimental as people at these events are always looking to try something new.”

Sagiryan from Ping Pong agrees: “Dim sum being bite-sized means it’s an ideal choice for street food; and we have the mixed dim sum boxes with traditional prawn dumpling, chicken and cashew nut, spinach and mushroom and prawn and scallop exclusively for the festival. We’re excited to see customers’ reactions.”

Indeed, street food tends to appeal to a certain kind of eater: someone who may not have time – or the inclination – for a full sit-down meal, but who is happy to dip a toe into an unfamiliar style before committing to booking an actual table.

“Street food has a massive appeal to the busy Londoner who just does not have time to go out for a long meal. People want to grab something quick, but also want to know that it’s from a reputable brand. This allows us to reach different types of customer,” Sagiryan continues.

And therein lies another advantage for street food operations that already have a permanent location: diners who discover a dish for the first time from a street food van might then seek it out later, long after the food festival or summertime pop-ups have gone.

Calling cards

In this way, offering a street food van is effectively a means to turn transient customers into restaurant regulars.

“Visitors to street food markets are coming to eat, and the question for them isn’t ‘Shall I eat?’, but ‘What shall I eat?’ And once they try at the events they often visit our stores,” says Hurley.

“It is an opportunity to reach out to new guests,” agrees Sagiryan. “The demographic of people attending [events such as] the Just Eat Food Fest will complement those who tend to eat at Ping Pong restaurants [and] while the danger with street food is that people might only visit that site once, with restaurants across London [customers] can then come to be entertained seasonally too.”

Similarly, with festivals such as Just Eat’s event, it also offers opportunities for further business, via the exploding take away and delivery market.

“The Food Fest is a great chance for our restaurant partners to showcase their diverse range of dishes to potential new audiences,” explains Graham Corfield, UK managing director at Just Eat. “We haven’t brought a selection [like this] together before.”

The sociable nature of street food also means festivals can also be a hotbed for interaction and communication – not just between business and diner, but between businesses themselves.

“It offers an alternative way to connect with people who may not have heard of your restaurant before, and raise awareness of it,” explains Berry. “And you actually have time to chat to your customers, meet fellow restaurateurs, and see how people respond to their concepts. In a restaurant, you might not get that opportunity.”

Dum Dum Donutterie’s Hurley agrees. “It has felt like a real team effort with JustEat and the other restaurants. The biggest challenge was just making enough doughnuts!”

As Sagiryan summarises: “Street food is accessible, inexpensive, personable, with the [ongoing] novelty of being served outdoors. Appetite for diverse and high-quality street food options shows no signs of slowing.”