Business Profile: Dishoom

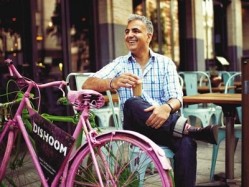

Do management consultants, bankers and accountants make good restaurateurs? Don’t answer that. Shamil Thakrar used to work for Bain & Co, the internationalmanagement consultancy giant that boasts Mitt Romney as its former CEO. His business partners have backgrounds in banking and accountancy, as well as the technology sector.

So you might expect Dishoom, their fledgling restaurant business, to be either a ruthlessly efficient numbers-driven operation, and/or a complete disaster. It is neither of those. The Indian-themed Dishoom, which is shortly to open its second site, is a restaurant loaded with romance, nostalgia, design personality and menu surprises. Co-founder Thakrar, who has an MBA from Harvard under his belt, is similarly un-stereotypical: a blend of creative vision, humility, erudition and evident business acumen.

“Focusing too much on the numbers and the P&Ls just doesn’t work,” says the 41-year-old. “You have to focus on making the experience brilliant. We were all new to restaurants when we opened [in Covent Garden in 2010], so all the learning had to be fast and up a steep curve.

“In fact, unlearning some of that finance and consulting and business school stuff has been really important. Sure, labour costs and food costs have to be under control, but it’s actually a business about people and food, which they can’t really teach.”

Despite the inexperience of the founders, who also include brothers Adarsh and Amar Radia, Dishoom captured the imagination of

Londoners from the word go. Directly inspired by the Irani cafés of Bombay, the site on Upper St Martin’s Lane operates in the under-populated

space between upmarket Indian restaurants and high-street curry houses.

The trio sensibly enlisted the expertise of a number of more experienced restaurant names – Robbie Bargh’s Gorgeous Group on the drinks side and consultant chefs Karen Anand and Stephen Parkins-Knight to help with menu development.

The result is an accessible all-day dining space over two floors with a distinct identity and excellent Indian food offering with the odd Anglo twist (eg bacon naan roll). The menu – overseen by well-regarded head chef Naved Nasir – remains proudly authentic in the main, numbering just a single curry dish each day and majoring on the likes of keema pau, dill salmon tikka and chicken berry biryani.

Cliché-free zone

Dishoom succeeds in its stated mission to dispel some of the clichés in this country surrounding Indian food. “The UK has a long and familiar relationship with India, which we can build on, but that relationship may have become a bit old and complacent. The curry-house tradition is peculiarly British and quite odd. We wanted to take a fresh look at things because Bombay food is not about curry,” says Thakrar.

The spectrum of dishes – and prices – is unusual in that diners can come in for chai and a snack or a multi-course meal with lobster and Champagne.

“We’ve actually had [billionaire] Lakshmi Mittal in here, sitting alongside a table of young hipsters,” says Thakrar. “We like that because it feels true to the source, where you might have a taxi-wallah next to a lawyer.”

The restaurant in Upper St Martin’s Lane now serves in the region of 3,000 people per week, with queues for tables most evenings. Average spend per head is £18 at lunchtime, hitting the £25 mark for dinner. “We’ve done a lot of work on the service flow – from the moment the customer comes through the door to them paying the bill – and the systems that support that,” adds Thakrar.

His cousin Kavi Thakrar, who joined as a co-director shortly after the first site opened, leads the day-to-day operational side along with restaurant manager Brian Trollip. Shamil takes the lead on design and marketing, as well as people management. “I take all new staff through our culture and heritage, and do some yoga with them too. We talk a lot about the idea of selfless service, as if they [the customers] were guests in your home. To get everything right, consistently, you have to be passionately focused.”

It is also promoting heavily from within for its imminent expansion; both Nasir and Trollip will expand their roles to oversee both sites on the kitchen and front-of-house sides respectively.

Dishoom has no formal centralised functions to speak of and the directors retain complete control, without having to answer to venture capitalists or private backers. The Thakrar family hails from Gujarat, north of Mumbai, while the Radias’ roots are in the city itself. All grew up primarily in the UK, but retain a deep connection to Mumbai. “I remember visiting a lot when I was young and going to these cafés with my grandmother,” says Thakrar. “A lot of those childhood memories have come to the fore here.”

Last summer, the team took up a five-month temporary residence on the South Bank under the guise of Dishoom Chowpatty Beach, a tongue-in-cheek take on the beach stalls of Mumbai’s seaside resort serving vadu pau (an Indian chip butty with chilli chutneys) and fruit cocktails. Its success served as a precursor to more long-term expansion, with the opening of the second Dishoom later this month.

“We’re not interested in banging out a formula, so we’ve changed the approach a little,” he says. “The design direction, the focus on the bar and even some of the new menu items all feel quite different [to Covent Garden]. I think people in Shoreditch appreciate new and different things too.”

Reclaimed elements

The most overt adjustment is in the design, with the company employing the services of restaurant specialist Russell Sage Studio to create a less slick, more eclectic space with a plethora of specific homages and plenty of reclaimed elements.

Situated on a block between Shoreditch High Street and Boundary Street in east London, it includes a covered courtyard seating 40, a ground floor with bar and café-dining room for 100 and a basement kitchen and dining room with a further 50 covers. Unlike the central London operation, it will house its own bakery – a personal passion of Nasir – which takes centre stage on the ground floor alongside the bar.

The bakery will turn out Bombay spiced biscuits and traditional puffs. The restaurant will also serve its own take on the upscale street food so popular in the capital right now: the lamb raan ‘burger’. A marinated leg of lamb is slow-cooked overnight, then pulled off the bone and served in a bun with sali [potato chips] and slaw. “Lamb raan is usually quite a special occasion dish, but I guess by putting it in a bun we’re democratising it somewhat.”

The basement will house the open cooking space and should feel like “you are sitting in your slightly dotty aunt’s kitchen”, according to Thakrar. The other key change will be the centrality of the bar, both literally and figuratively. In Covent Garden, the basement bar effectively acts as a holding area for those waiting for tables, as opposed to a destination in its own right. In Shoreditch it will take pride of place on the ground floor, with a cocktail programme that Thakrar describes with unbridled enthusiasm.

“We’ve taken the idea of a 1940s bar in Bombay and played with it, so we’ve focused on vintage colonial drinks like flips, sours, gimlets, fizzes and juleps. We’ve even invented our own Indian bitters. We also discovered a punch recipe from 1694, which we’ve called the Presidency Punch, served in traditional punch bowls, and created a drink called Edwina’s Affair – referencing Edwina Mountbatten’s scandalous relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru.”

It promises to be an intriguing – and unique – addition to the burgeoning east London food and drink scene. While many earmarked Dishoom, after its initial success, as having the potential to become a premium chain in the making, the founders’ passion for authenticity and originality may preclude that.

“Perhaps next time we’ll look at the literary and arts heritage of the Bombay cafés, but we’ll only do another if we’ve got something new and interesting to say.” So far, so interesting.

This article first appeared in the October issue of Restaurant magazine. Subscribe here.